The basic idea behind Blech – A practitioner's point of view

Application example: UART communication

Let us consider a simple embedded use case. We want to implement a UART communication. For the sake of simplicity, we focus on the data transmission only. Given a number of bytes in a data buffer, the job is to physically send them via the serial interface one after the other.

The implementation is to be done on the bare metal; no operating system, no fancy hardware abstraction layers or library functions. That means that, in our example, the UART peripherial is directly controlled via its hardware registers. Writing a byte to the register UART1->DR causes the UART hardware interface to send that byte over the wire. While the transmission is in progress, the flag UART1_FLAG_TXE is true. The interface will automatically set the flag to false after it has finished sending the byte. At that time, it can also trigger an interrupt to indicate that the job is done.

Apart from the sole functional correctness it is important that the application is generally compatible with the stringent constraints of the embedded domain. That is, very limited resources – computation time and memory – and possible realtime requirements. Keeping the embedded software reactive is key in order to handle realtime-critical events in time.

Below sections discuss different implementation schemes in C and Blech for realizing the buffer transmission.

Implementation schemes in C

In the following section we consider the pros and cons of two popular programming styles for implementing the UART communication in C. The focus is on software engineering and suitability for the embedded domain.

The blocking style

Let us assume that we – as software developers – do not have any experience in writing embedded code and we do not know anything about the stringent constraints imposed by the embedded domain. We just (naively) start by implementing a function send_buffer that encapsulates all the details required for data transmission. This approach is reasonable and natural because this is what we have been taught in school and at the university. Motivated by several fundamental software engineering principles such as abstraction, separation of concerns, encapsulation and so forth we develop the solution below:

|

|

We pass the buffer and its length to the function. Then, we loop over the buffer. For each byte, we first wait for the UART device to become ready, second copy the next byte into the UART data register and third check whether or not we have reached the end of the buffer – it is as simple as that.

In this approach, everything related to the transmission is local. With local I not only mean the data in sense of local variables. I also mean the code – the knowledge – that is required to describe all necessary steps that have to be done. This makes it not only easy to comprehend how the transmission actually works but also facilitates its usage, debugging and maintenance. If something is not working as expected or if we want to change or extend the procedure in some way we know that send_buffer is the sole code block to look at.

However, there is a high price to be paid in order to obtain above encapsulation benefits. If we want to encapsulate the transmission of an entire buffer – and not only of single bytes – a call of send_buffer must inevitably outlive the transmission of multiple bytes. For this, its code has to be implemented in a blocking fashion so that it does not terminate once a single byte has been sent out. This becomes apparent from Line 5 in which we wait for the UART device to finish the transmission of the current byte. A while loop polls the corresponding UART flag in order to block the control flow of send_buffer before it proceeds with the next byte. The runtime behaviour of send_buffer is exemplarily depicted below:

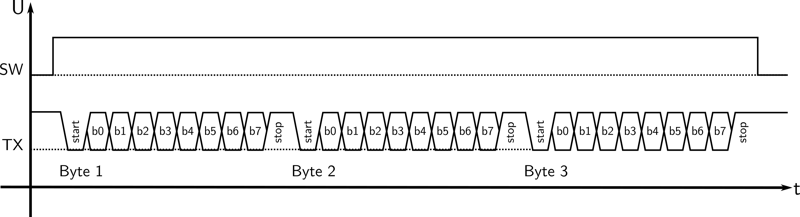

Exemplary scope capture of three byte transmission with software in polling mode.

Above example scope capture shows the transmission of a 3-byte buffer. SW indicates when the CPU is busy (SW -> HIGH) with executing send_buffer while TX shows the physical output signal of the UART hardware. It is easy to see that the entire processing time is eaten up by send_buffer until the last byte has been sent out. This causes several drawbacks:

- The thread calling

send_bufferis blocked for anything else. No other code can run concurrently so that- no other concerns of the embedded system can be processed.

- no other (important) events can be handled meanwhile.

- The CPU continuously runs at full speed leading to high consumption of processing time and energy.

- The call stack of

send_bufferis not freed so that memory cannot be reused for other concerns meanwhile.

Remember that, depending on the UART baudrate and the length of the buffer, above conditions can be true for a significant period of time. Consider a typical UART baudrate of 115.200bit/s and a buffer length of 1024bit. In this case, one execution of send_buffer would already block your software for 8.88 milliseconds – a small eternity in the embedded domain! Thus, in sum, this approach leads to poor reactivity and high resource consumption.

Conclusion

As a conclusion we can say that the blocking style makes it generally

- easy to fulfil software engineering principles.

- hard to fulfil constraints of the embedded domain.

The event-based style

Due to above limitations, practically all embedded software solutions decide in favour of the stringent embedded constraints and follow a non-blocking, event-based style instead. In this approach, code is executed only if necessary. That is, whenever an event – a noteable change of the environment – has happened.

Event-driven behaviour, however, is not supported by C on language level. Typical workarounds rely on statemachines and callbacks that are executed in an asynchronous-concurrent fashion. See the example below:

|

|

In this solution, send_buffer is only used to initiate the buffer transfer. It waits for the UART device to become ready, saves the buffer, its length and a transmission counter as global variables, and finally writes the first buffer byte into the UART data register. Then, in contrast to the blocking style above, send_buffer immediately terminates although not even a single byte has been actually transmittet yet.

Once the first byte has physically left the UART device, the hardware automatically executes the interrupt service routine in Line 12 which picks the next byte from the buffer and triggers its transmission. This process repeats for each byte until the entire buffer has been transferred. Ultimately, the buffer transmission is driven by a chain of callbacks that advances the progress step by step. The corresponding runtime behaviour of this approach is shown below:

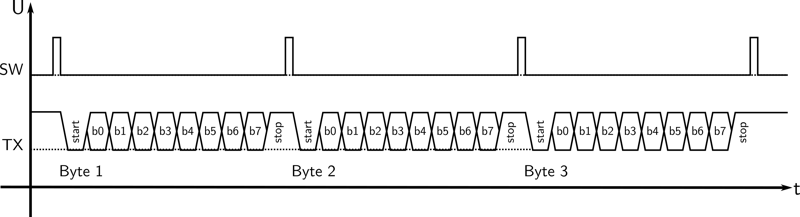

Exemplary scope capture of three byte transmission with software in event-driven mode.

This time, the CPU is only busy when a new byte transmission is to be triggered. Meanwhile it could either process other concerns, react on other events or go to sleep in order to save energy. Since send_buffer terminates after each byte its stack space is freed and can be easily reused for something else. By this, the event-driven approach perfectly fits the embedded domain.

However, all the valuable software engineering benefits of the blocking approach are gone. The functionality “buffer transmission” is now torn apart a function, an interrupt service routine and a set of global variables. This eliminates locality and requires me – the software developer – to implement manual stack and state management in order to maintain the program state across several function and ISR calls respectively.

Note

Remember that stack and state management are actually low-level tasks done by the CPU , using a program counter and a set of working registers, in order to reduce the burden of the software developer. Now, with statemachines and callbacks, we have to do this tedious and error-prone job in my high-level programming realm – doesn’t that sound kind of inherently contradictory and counterproductive?All the data (the stack) that has to outlive multiple function calls, e.g. the pointer of the buffer, the buffer length and the transmission counter, have to be stored in global memory. The latter by itself entails a whole line up of engineering drawbacks. In addition, the asynchronous event-driven execution of send_buffer and the interrupt service routine provokes concurrency bugs and non-deterministic runtime behaviour by design. By the way, what will happen if send_buffer is called while a buffer transmission is still ongoing?

The progress of the program (the state) is encoded in a statemachine that advances on each event. On the one hand, statemachines are generally a very efficient and well understood technology in order to describe and execute event-driven behaviour for and by machines respectively. But, on the other hand, statemachines are less suitable for humans, especially when it comes to readability and comprehensibility.

In statemachines, state is explicit while control flow is implicit. This makes it easy to generically describe and perform single computation steps by transition tables based on the current state and the current input. But for us – as software developers – this is not the natural understanding with what we have grown up. We are used to write code in a sequential fashion in which control flow is paramount. State is only implicitly given by the current code line that is to be executed and the set of variables. When looking at a statemachine implementation, irrespective of whether it is given as C code or a graphical drawing, it is generally difficult to comprehend the sequence of decisions and commands that have to be taken and executed in order to realize a certain functionality.

Finally, think about how you would establish automated tests for this kind of code. You could write unit tests for each of the functions – which is by itself not easy because they internally rely on global variables – but this only covers the behaviour of your software on a per event basis. With this approach, it is really difficult to systematically test the behaviour over time across several reactions. Not only because the code is highly distributed but also because the runtime behaviour is inherently non-deterministic and hence not reproducible.

To sum it up, the event-based style encourages software solutions that are difficult to program, comprehend, test and maintain.

Conclusion

As a conclusion we can say that the event-based style makes it generally

- hard to fulfil software engineering principles.

- easy to fulfil constraints of the embedded domain.

Lifting the abstraction level – the pseudo-blocking style

Looking back to above implementation schemes the following becomes apparent:

- The blocking style, on the one hand, typically leads to good software quality but is generally not applicable in the embedded domain.

- The event-driven style, on the other hand, perfectly matches the stringent embedded constraints but it seems that we figuratively fallback to a lower level of programming.

What if we lived in a perfect world where we could cherry-pick and combine the advantages of both approaches? – Welcome to Blech!

Basic Idea

The basic idea behind Blech is to let the software developer write code in a blocking fashion (good software quality) and systematically compile it into an efficient, deterministic, event-driven statemachine implementation (fit embedded domain). By this, Blech code allows to recover all the software engineering advantages mentioned above and, at the same time, fulfills the stringent embedded constraints. This combination is usually hard to achieve and makes Blech lifting embedded programming to a higher level of abstraction.This concept is what I call the pseudo-blocking style. Your software looks and logically behaves like blocking code but is actually non-blocking under the hood. On the bare metal, it can easily interleave its execution with other synchronous or asynchronous parts of your software. For example, there could be some cryptographic algorithm asynchronously running in a background task while your Blech program continously reacts on incoming events.

The following code snippet shows how the buffer transmission can look like in Blech:

|

|

In the first four lines we declare the signatures of two external C functions that can be called by Blech in order to actually interact with the UART hardware. After that, an activity is used to encapsulate all the data transmission code. We pass the buffer and its length as parameters. A repeat loop is subsequently used to

- suspend the activity until the UART is ready for transmission (Line 11).

- write the next buffer byte to the UART data register (Line 12).

- repeat from (1) until the end of buffer has been reached.

Note

In the C environment,ISR (UART1_TX) is used to generate an event for triggering the Blech program. This means that await uart_isReady() will return as soon as possible after a byte has been transmitted – we do not have to wait until the next periodic sysTick for instance.

You may have already noticed that this solution looks very similar compared to the blocking style above. In fact, it has all of its software engineering benefits but none of its drawbacks. Above Blech code is translated by the Blech compiler into an event-driven state machine implementation that only logically simulates the blocking behaviour of await for the software developer while your code actually remains reactive all the time. By this, the Blech solution effectively combines the advantages of both implementation schemes known from C.

Conclusion

As a conclusion we can say that the pseudo-blocking style makes it generally

- easy to fulfil software engineering principles.

- easy to fulfil constraints of the embedded domain.

Concurrency in Blech

Concurrency is one of the key concerns in embedded programming. The traditional, asynchronous execution style of concurrent threads is known to induce a line-up of engineering problems such as race conditions, data inconsistencies, potential deadlocks and non-deterministic runtime behaviour. In Blech, however, all these issues are eliminated by language design due to the synchronous model of computation.

Let us slightly extend above example. We want to make an LED blink on every system tick, e.g. every millisecond, while a buffer transmission is in progress. At this point, we are aware that blinking an LED with such a high frequency is generally not useful since it is not visible for the human eye. Here, we just use it for demonstration purpose to show how easy it is to express concurrent behaviour by taking advantage of Blech’s cobegin statement:

|

|

In SendBufferBlinking, we just need to run the existing code of SendBuffer in one trail of the cobegin and add a second, concurrent trail that is responsible for flashing the LED – that’s it. The second trail is weak so that it will be aborted as soon as the buffer transmission in the first trail has been completed. Note that sysTick is a new input which provides the system tick event for switchting the LED on and off.

Concurrency versus single-threaded C code – a contradiction?

At this point, when people read that any Blech program is compiled into single-threaded C code, they are sometimes slightly confused. On the one hand, Blech advertises language level support for describing concurrent behaviour but, at the same time, it produces sequential, single-threaded code only. So how can that even work?

In order to understand this we have to distinguish between two different designs of concurrency. First, physical concurrency aims to increase reliability and / or performance by running software on real parallel or distributed hardware platforms, e.g. multi-core architectures, at the same time. Second, logical concurrency aims to provide a convenient and natural way to compose a system as a set of parallel, cooperating components. Physical and logical concurrency can be the same – but they do not have to!

Blech, in its current development state, allows to express logical concurrency only. The long term goal, however, is to provide support for multi-core systems and hence physical concurrency on language level too. Nevertheless, the existing feature set of Blech is powerful and beneficial already today.

Single-core applications

Single-core hardware architectures exclude physical concurrency by design. This means that, even with asynchronous threads, it is impossible to execute two commands concurrently at the same time; the entire software is strictly sequential. As a consequence, on single-core architectures, Blech has no disadvantages compared to conventional solutions with respect to concurrency.

Quite the contrary, in Blech the sequentialization is done systematically during compile time based on the synchronous model of computation – no non-deterministic scheduling decisions during runtime; no arbitrary interleavings of concurrent code; no race conditions and data inconsistencies. Finally, this leads to sequential code with deterministic and reproducible runtime behaviour – the major advantage that makes Blech outperform conventional, asynchronous languages in the embedded domain.

Multi-core applications

In multi-core applications where physical concurrency is mandatory Blech is still applicable. Considering a dual-core processor for example, we can have two instances of either the same or different Blech programs where each of them is running on a different core! By this, we basically create two synchronous islands – so to speak – that locally benefit from executing synchronous code while, from a global view, running asynchronously with respect to each other. This solution is particularly suitable for applications in which the concerns handled by core A constitute a high independence with respect to those of core B and vice versa.

What we cannot express in Blech today is concurrent runtime behaviour across multiple cores. That is, the cobegin statement cannot be used to describe how two concurrent trails, for example, are to be deployed, started, executed and rejoined across two different processor cores. But remember that this is not possible with threads too! The notion of threads does not say anything about how data and control flow is shared between multiple, concurrent hardware architectures.